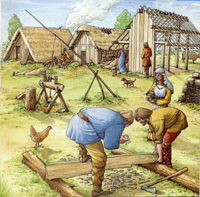

Village scene 1985

Quick links on this page

Saxons take over 442

Arthur leads resistance 470's

Battle of Badon 495

Gildas writes History 538

London and St Albans fall 570

Raedwald rules 599

Sutton Hoo burial 625

King Sigbert sponsors Felix 631

St Audrey's Ely nunnery 673

South Elmham Minster 680

Beowulf written 713

Bede writes History 731

|

The Political Context

Outside influences around our West Stow Anglo-Saxon Village

| c.367 - 370 AD |

Picts and Scots raided Britain in the North while Saxons raided in the South and Theodosius had to come from Rome to restore order again.

|

| 410 AD |

The Romano-British people were told to look after themselves without the aid of Roman soldiers as the army had been taken to Gaul in 406.

|

|

411

|

The Gallic Chronicle of 452 reports a dreadful Saxon raid on the Channel coasts in 411.

|

|

428

|

The British appealed to Rome for help to defend themselves against the Picts in the north-east and the Irish in the Severn Valley but no help was available.

So the Council met under Vortigern and decided to appeal to the 'Nobles of Anglekin' for aid. They intended to hire some Saxon seamen to defend the coasts just as past Roman emperors had done. The Saxon leaders were Hengest and Horsa, and three keels or ships were sent with them and they were based on the Isle of Thanet. There were probably only a few hundred of them at this time. They were paid by a monthly system of supplies.

|

|

Runic gaming counter |

|

430

|

After a short time the number of Saxons allowed to settle increased and new areas were penetrated. Very early remains have been found at Caistor by Norwich, Luton and Abingdon. This roe deer foot bone was excavated at Caistor by Norwich, and was used as a gaming counter. The runic inscription indicates that it was of north german origin, showing evidence of the new language penetrating British life. The runes spell "raihan", meaning roe deer, and such cryptic inscriptions typify the earliest runes found in this country.

These were strategic defensive settlements, established to protect the British Cotswold heartlands, and Norfolk was particularly well settled by these Saxon merceneries. Because the north still had the army in place, there was less need for reinforcements to be sent there. Forces were placed to protect the North road, the Thames estuary and the major intersections of the Icknield Way. These inland posts were really a defence line of last resort.

One of these posts might have been at West Stow, sitting on the River Lark crossing of the Icknield Way.

Just two miles to the west there was an important, large and apparently undefended settlement at Icklingham which continued to be occupied until the very last years of Roman Britain.

In the east and south, Germanic forces were accepted nearly everywhere, with the exception of Verulamium, the capital of the Catevellauni.

In the absence of a Pictish or Irish attack, the Kentish Chronicle reported that Hengest and Vortigern invited Germanic reinforcements under Octha to bring 40 ships over to attack the Picts on their own territory. They plundered the Orkneys and then settled in North Northumberland.

|

|

437

|

By using these Saxon fighters retained to fight on his side, Vortigern produced a prosperous Britain, with secure borders, only to be overthrown by civil war when another British nobleman, called Ambrosius, saw his chance. With peace, the taxpayers began to refuse to pay for the Saxon defence and the Council tried to send them home.

In 437 it appears there was a battle between Ambrosius and Vortigern possibly at Wallop in Hampshire.

Vortigern had to rely on bringing in a further 19 ships of Saxon reinforcements to defend himself against Ambrosius. They seem to have been settled, together with later arrivals, in and around Canterbury and East Kent. Therefore, far from reducing the numbers of foreign mercenaries, British civil war served to increase their numbers.

|

|

Anglo Saxon 'keel' |

|

442

|

More and more boats were arriving from the Continent. There was pressure on the Saxon's homelands from new settlers from Denmark and Holstein, and flooding from the rising sea levels. One such boat, constructed of larchwood, was found buried at Ashby Dell in Suffolk in 1830, a few miles from Burgh Castle. It may have arrived there at a time when the valley was actually a waterway, for sealevel was rising during the 5th century. Its construction is similar to the Nydam boat, excavated in Denmark. A reproduction of the Nydam vessel is shown here.

Hengest's Saxon forces had now increased to such a level that resentment over their spread and their pay rose high on both sides. Hengest demanded more money and more land for his growing forces. Whatever happened, it became a fight and armed Saxon insurrection swept across the lowlands. Vortigern was first driven out of Kent by Hengest.

Later, Caistor by Norwich for example, was totally destroyed, as undoubtedly were other settlements, and Colchester was stormed. The economy was also destroyed. The pottery industry ceased production. Farms ceased to produce food, and markets ceased to operate. Certainly Kent and East Anglia were conquered in this first attack.

The way was now clear for Saxon soldiers to summon their relatives and their families to join them in the east of Britain.

|

|

446

|

The Romano-British appealed for help to Gaul, the great General Aetius, and said they were being pushed out by barbarians, and also suffering from widespread flooding. This letter has been called "The Groans of the British". The Saxons attacked right across to the West, but appeared to withdraw to their eastern settlements again after great destruction of the economy.

Aetius provided no help, but Bishop Germanus visited the British for a second time, so we can envisage the country more or less partitioned into Saxon control and old British control with a largely Romanised flavour.

|

|

452

|

Around this time the British launched a counter-attack upon the Saxon encroachments.

Vortigern's son, Vortimer, was said by the Kentish Chronicle to have driven the Saxons out of Kent and back to Thanet for five years. The main battle seems to have been at Richborough.

The British also won at the Battle of Aylsford, but at Crayford the Saxons won and drove the British out of Kent, back to London.

The Saxons now "summon keels full of vast numbers of warriors" to give reinforcements in what was to become full scale warfare.

We do not know if the local Anglo-Saxons at West Stow joined in any of these battles, but they must have stood ready to fight over a period of decades.

|

|

458

|

From their bases in Kent, Norfolk and the Cambridge-Newmarket region the Saxons attacked the rest of Britain in a great raid as far as Wales. London remained in British hands. By now, many Saxon villages were at least 20 years old and the young men were born in this country and were in effect fighting for their homes and families, not considering themselves invaders. Young men of Stowa would very likely have become involved these actions.

|

|

470's

|

Ambrosius Aurelianus was succeeded as the main leader of the surviving Romano-Britons by Artorius, another man of Roman family, known to us today as King Arthur. This is the real period of Arthur, a relic of the fallen Roman Empire, hanging on against the Saxons constantly encroaching from their new homelands in East Anglia. The British retained a knowledge of literacy, and of Christianity, whereas the Saxons must have seemed totally alien, with their pagan practices, and contempt for books and the ways of "civilisation".

It seems likely that British resistance in 470 was based on the wealthy farmlands of the Cotswold area, Salisbury Plain and in Hampshire. It is also highly possible that they based their tactics upon the use of horses and mounted cavalry. This knowledge may have been remembered from Roman days, or invented by necessity, but their armour and weapons would be have been Roman. The Saxons at this time invariably fought with spears on foot, and this helps to explain how the weakened British managed to resist them for so long. Using mounted men in hit and run attacks, they could also cover large amounts of territory at five times the speed of the Saxons.

The Anglo-Saxons named their country Englaland (land of the Angles) and their language was called Englisc. It is the modern historian who refers to them as Anglo-Saxons, who spoke Anglo-Saxon or Old English. Suffolk is full of Anglo-Saxon place names, most names coming from Old English words.

Latin writers referred to them as Angli and were doing so before the middle of the 6th century.

|

|

480

|

At about 480 Cerdic was commander of Saxons in the Winchester - Southampton area. They fought in the Battle of Portsmouth Harbour against Arthur and the British. This was probably at Portchester, the most westerly of the old Saxon-shore forts. The battle seems to have had no decisive outcome.

The flow of Germanic immigrants much increased in the late 5th century, to such an extent that the homeland of Angeln was deserted in Schleswig. At this time we believe that the Kings and their courts also moved to England.

In the Ipswich area a group arrived with a strong Scandinavian background, and Danish traces are recognisable in the archaeology of Kent.

|

|

490's

|

London and its surroundings remained a British stronghold separating the Saxons of Kent from those in East Anglia. This situation seems to have persisted up to 568.

The Saxons themselves were not a homogeneous group. Differing grave goods found in their cemeteries indicate that some settlements contained markedly different cultural backgrounds from others, even when comparatively close to each other. For example, at Haslingfield, a village in sight of Cambridge, these people seem to have had no contacts with Cambridge Saxons.

|

|

495

|

The final battle of this era was the Battle of Badon Hill (Mons Badonicus according to Gildas). The English King Aelle led the Saxons from Kent, Sussex and Wessex and seems to have advanced westward to attack British cavalry bases. Badon may be at or near today's Bath such as Solsbury Hill by Batheaston, but its exact site is unknown and hotly disputed. According to Nennius, there was a 3 day siege which ended when King Arthur led a charge and killed 960 Saxons. Following victory at the Battle of Badon, won by the British, peace lasted for 75 years.

The difficulty of establishing accurate dating in the 'Dark Ages' is shown by this battle, which some historians date to 516 or 518. It is best thought of as occuring shortly before or after the year 500.

|

|

Gold pendant from Undley |

|

500

|

By now the war in England had been fought to a standstill, with partition of territory being an established fact. Eastern England, and East Anglia in particular, was firmly held in Saxon and Angle hands.

Trade and social contacts were probably maintained with their homelands, as shown by many of the objects that have been found. At Undley, near Lakenheath, a high status Angle wore this gold pendant shown here. It was made in the late 5th century in Schleswig or southern Scandinavia. A roman helmeted head copies many Roman coins, and although the wolf and infants is a strong Roman motif, there are also runic characters present. Such a pendant, made from a pattern stamped into flattened gold, is known as a bracteate.

In the Fens the Roman drainage system built around Car Dyke had failed as there was no administration to maintain it against the rising sea levels. Areas of Fen now flooded, leaving only Ely and a few other islands above the water level. Along with this problem came a rise in sea levels through the 4th and 5th centuries, so that by this time East Anglia was a virtual isthmus, cut off from the area of Mercia to the West by the great marshy fenland.

To the south the heavy clay soils of the Stour valley were reverting to Wildwood. The Roman roads were becoming overgrown by impenetrable blackthorn thickets by a lack of use and maintenance. Rome's once great city at Colchester declined into a ghost town by the 6th century, and both Colchester and the area of North Essex would be sparsely populated until the coming of the Danes in the 10th century.

|

|

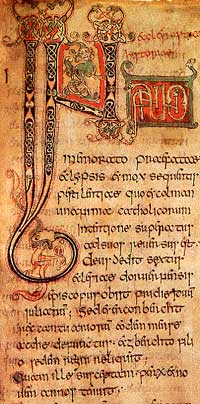

6th century village life |

|

525

|

After this date a further wave of settlers came to East Anglia and Kent from Sweden via Denmark and Friesland. If it was around this time they may have been led by Wehha, because the first King of East Anglia was Wehha according to Nennius, a 9th Century historian.

|

|

538

|

Around the year 538, Gildas wrote his 'complaining book', which was an attack on the princes and bishops of his day. He tried to look at history to find the origins of the evils he perceived. Gildas was born in the kingdom of the Clyde but was taken south to the shores of the Severn Sea and was taught in the old Roman educational tradition. Gildas tried to explain why the British were being punished by being occupied by Anglo-Saxons and why they deserved this fate.

|

|

540

|

If there were new settlers at this time they presumably were led by Wuffa who would have been the second East Anglian Anglo-Saxon King after Wehha. He sailed up the Deben to found Ufford and the Wuffinga dynasty. These people had a considerable impact despite the fact they were preceded by 100 years of continental settlement. With a strong maritime tradition they practised ship burials at Sutton Hoo, Snape and Ashby. The descendant royal family is known as the Wuffings or Wuffinga. The dynasty is thought to have continued with Tyttla, and then to Raedwald, the most famous and greatest of them.

The area later known as the Wicklaw, and later as the Liberty of St Etheldreda, may have been the home estates first established by the Wuffing kings. It covers all their major sites from Rendlesham to Sutton Hoo, and the estuaries of the Deben and Alde and south to the Orwell.

By now East Anglia seems to have become one cohesive kingdom. A strong king would be welcome to impose order in the land and to create the stability without which the farmers could not till the land successfully.

In these early times the King would have lived off the proceeds of his own estates. In addition, there arose a system called "food rent" or "feorm", whereby the King was supplied with food and provisions by each group of settlements in some agreed form. This may have arisen as the King moved his entourage around his kingdom, perhaps spending periods at designated royal "vills" or settlements. In the absence of money, these food rents were paid as real provisions. Each settlement also owed their lord a variety of services, mainly a mixture of agricultural and military duties.

|

|

Anglo Saxon horse burial |

|

550

|

Around 550 a Saxon nobleman was buried with his horse at Eriswell. The site was discovered in 1997 under a baseball pitch scheduled for redevelopment on the USAF base at RAF Lakenheath. Some 200 graves were located on the site, spanning a period of 150 years. This is now a completely different form of burial than the earlier cremations exemplified at West Stow.

|

|

563

|

By about 560 the era known as the Great Migration period had largely ended. The Yellow Plague of 547 to 551 may well have helped to end much more movement of populations.

Outside East Anglia, there were the kingdoms of Kent, the Jutes in the Isle of Wight, the East Saxons and the West Saxons. Other Germanic or European kingdoms were established across England by the 7th Century.

|

|

570

|

The second Great Saxon uprising led to the English mastery of the area called England today. The old British way of life, hanging on in the Midlands, was ended when Verulamium (St Albans) and its surrounding parts of the Chilterns were finally conquered by the Anglo-Saxons. It also appears that the British stronghold of London and its surroundings was finally over-run around this time.

The Saxon's pagan culture would be unchallenged in England until about 630, when Christian missionaries started to impress the Saxon kings. However, the pagan culture was itself in a state of evolution. Early on the preferred death ritual was burial of cremated remains in an urn. Burial of the body with grave goods was now more prevalent, and in some high status cases mounds were being thrown up over the grave. The Anglo-Saxons had found many earlier period Bronze Age mounds, and had sometimes used them for their own purposes.

At Snape and nearby Sutton Hoo new burial rites incorporating ship burial within a prominent mound were evolving.

|

|

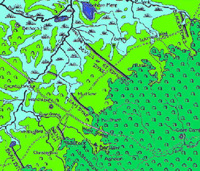

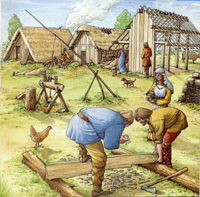

Defensive dykes on Icknield Way |

|

c.575

|

The Devil's Dyke at Newmarket, and the Fleam Dyke, a few miles further to its south west have long been believed by some historians to date from around this time to defend from attack from the west. Recent detailed work has confirmed that these earthworks date from the 5th to the 7th centuries. They are also aligned to face an attack from the south west. There are other earthworks within the area of the East Anglian kingdom, such as Black Ditches on Cavenham Heath and Risby in Suffolk, and the War Banks at Lawshall. These may have more obscure origins.

Only a great king of a prosperous nation could undertake such feats of engineering. Whether the young men of West Stow and the other Lark valley villages were involved in the construction of such defence works must at present remain in our imaginations.

|

|

578

|

Roger of Wendover, writing in about 1235, recorded that Tyttla now ruled over East Anglia, presumably following the demise of Wuffa. Bede, in about the 720's, also noted Tyttla as the father of Raedwald and Enni. Wuffa himself may have been one of the very first to be buried under a mound at the newly founded aristocratic grave site now known as Sutton Hoo.

|

|

580

|

In 580 or a short time before, Anglo-Saxon King Aethelberht of Kent married Bercta, or Bertha, the daughter of the Frankish King, Charibert of Paris. Most of the kingdoms just across the Channel from England were Christian, and the English kings would have been well aware of that religion, even if they kept their own traditional beliefs.

As ties grew with the continent it is not surprising that late in the 6th century Merovingian Frankish gold coins reached our shores and a purse of such coins was found at Sutton Hoo. No Anglo-Saxon native coinage existed at this time.

|

|

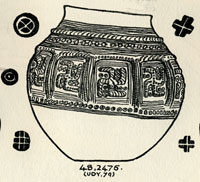

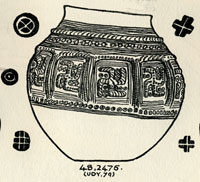

Lackford Cremation Urn & potmarks

|

|

585

|

In 1947 T C Lethbridge excavated a pagan Saxon cemetery at Mill Heath, Lackford. The site is above the 50 foot contour on a peninsula of land between the south bank of the River Lark and the Cavenham Mill stream. He found between 400 and 500 cremation urns, a concentration which is unusual for the Lark Valley, where earth burials, or inhumations, are more prevalent. There were swastikas present upon a number of cremation urns, and the Anglo-Saxon cemetery at Lackford has yielded some of the most exquisite designs of this image.

Lethbridge called some of the pottery the Icklingham type, as he assumed that Anglo-Saxon potters had used the same local clay as had the Romano-British potters who had left kilns at Icklingham and on West Stow Heath. For some years the Icklingham potter has also been identified as the Illington/Lackford potter. He has been known to have working during the late-sixth century somewhere along the west Norfolk/west Suffolk borders. His output was cinerary urns of a number of standard types decorated in two or three routine styles. Decoration was stamped on to the vessels while they were still damp. One of these stamps has been found and it was made out of a red-deer antler and bore a cross die. Stamps frequently used by the potter, or potters, were a cross-in-circle, a St Andrew’s cross and a concentric circle with a blob centre. Decoration in the main was restricted to pots used as cinerary urns. Distribution of the products was roughly within a radius of some thirty miles centred on Lackford with one outlying example some eighteen miles further on at Castle Acre in Norfolk.

We do not know what the relationship was between the village at West Stow and the Lackford cremation cemetery, but there must have been close connections of some kind or other. Many more cemeteries have been found than settlements, simply because human remains and grave goods have been more easily identified than the soil marks remaining from decayed dwellings. Thus we know of cemeteries at Lackford and in Bury at Northumberland Avenue, Barons Road and Westgarth Gardens, but do not know where their settlements lay.

|

|

597

|

Augustine finally arrived in Kent on his mission from the Pope. He was met by King Aethelberht on the Isle of Thanet, where Aethelbert had given them permission to land. This seems to have resulted from Athelbert of Kent being married to Bercta, or Bertha, his Frankish princess from Northern Gaul, who was a Christian. She was asked by Pope Gregory to use her influence on the King and paved the way for Augustine.

At first Aethelbert confined the Christians to Thanet, and when he did meet them, he travelled to the Island himself, rather than summoning them to his own halls. He spoke to them out of doors, a position which Bede said was to avoid the possibility of witchcraft.

Aethelbert, at first, refused to accept the Christian message, but he permitted them to preach throughout Kent, and soon allowed them to set up home in Canterbury, where the King himself lived with his Christian wife, Bercta.

Augustine and his entourage began to build and restore the remnants of Roman churches, and began to convert the population of Kent to the Roman form of Christianity. He brought 40 monks with him and at Christmas 597 some 10,000 people were baptised in Kent. Canterbury would become the home of English Christianity from this beginning.

Athelbert was rising to become High King of England and political refugees seem to have been accepted at his court, including Raedwald, later to be King of East Anglia. Raedwald possibly converted to Christianity in Kent at this time. Politics at this time was sometimes a violent power struggle and those on the losing side often fled to other kingdoms. In this respect the Anglo-Saxons were much like the Romans.

|

|

How Raedwald may have looked |

|

599

|

With Christianity rapidly being adopted in Kent, and Aethelbert of Kent rising in power beyond his Kentish borders, Tyttla of East Anglia died.

The mighty Raedwald returned to East Anglia and took over his Wuffing inheritance as their king and seems to have ruled over all East Anglia. Bede recorded that Raedwald ruled East Anglia from Rendlesham in East Suffolk.

|

|

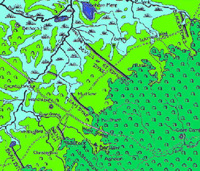

Wuffing kingdom of East Anglia |

|

600

|

By this time, the East Anglian kingdom of the Wuffinga dynasty was independent, powerful and economically successful. But the threat from Mercia in the west was increasing. Gipeswic, or Ipswich, was probably set up as a trading post around 600, and would quickly develop through the century, becoming a major port and industrial centre. Raedwald may have been involved in establishing Ipswich.

The life of people in small villages like West Stow was inevitably now going to be influenced by the factors of a strong new king, the arrival of Christian missionaries, and the beginnings of growing townships. The King and his court exercised more and more authority over everybody's lives.

As time passed the system of government became more formalised. The way in which the king received his "feorm" or food rent was, no doubt, refined by local moots or councils. The military service owed to the local lord and to the king was also refined, so that each district had to find a specified number of fighting men for the "fyrd", or military levy. These duties would require areas to be grouped together in some formal manner, which would later evolve into the "Hundreds", which survived as units of local government into modern times.

|

|

604

|

According to Bede, it was in the year 604 that King Raedwald of East Anglia converted to Christianity.

By at least 601 King Aethelbert himself had converted to Christianity and he wanted his allies to join him. Both Saeberht of the East Saxons and Raedwald cemented their relationship with the Bretwalda Aethelbert, by travelling to Kent to be baptised and to take Holy Communion. St Augustine himself may have baptised Raedwald in Canterbury. Augustine also consecrated Mellitus as the first Bishop of London, with his seat at St Paul's, to minister to the East Saxons. It seems likely that Augustine would have wanted to appoint a Bishop into Raedwald's East Anglian realm as well. Perhaps Raedwald was not ready to accept such a posting at this time.

Raedwald was to become notable because he would set up a pagan altar and a Christian altar within one temple at his home, and seems to have trodden his own fine line between the old religion and the new. In any case, Raedwald's Christianity was the first to be established north of the Thames, and despite his temple of two altars, Christianity would become the established religion for the future.

|

|

616

|

By the end of the year 616 it must have seemed that Christianity was in full retreat in England. The sons of King Aetholbold of Kent and King Saebert of Essex had not embraced Christianity when they inherited their kingdoms. Pagan King Aethelthryth of Northumbria was advancing south and threatening Christian areas. Only King Raedwald with his two altars was still ruling in England as a Christian King. Archbishop Laurence, Bishop Mellitus and Bishop Justus of Rochester now decided to abandon their mission to Britain, according to Bede. Apparently they did not leave, and Bede also recorded that it was the example of Raedwald that eventually would bring King Eadbald, and his kingdom of Kent back into the Christian fold.

|

|

Possible Hall at Rendlesham |

|

617

|

Raedwald did not wait for Aethelfrith to carry out his threat of war. Instead, he went on the offensive and led his army north as far as the River Idle, south east of Doncaster, on the southern edge of Aethelfrith's kingdom. We may imagine that the fighting men of all the small villages in the Lark Valley, including West Stow, would have been called up to join the fyrd or army.

Raedwald's army was in three columns, and the Northumbrians managed to destroy one column, killing Raedwald's son in the process. The other columns, led by Raedwald, stood firm against Aethelfrith and finally defeated his army after killing him.

The Anglo Saxon Chronicle recorded this event many years later as follows:

.

"Here Aethelfrith, king of the Northumbrians, was killed by Raedwald, king of the East Anglians, and was succeeded by Eadwine."

This battle gave Raedwald enormous new power in the country, although his son, Raegenhere was killed in the process. Edwin was given Northumbria as a client king of Raedwald. As the old King of Kent, Ethelbert, had died the year before, Raedwald was now acknowledged as the English Bretwalda. This meant he was the High King, with his power extending even into Northumbria. No previous English King had been so powerful, and the message would have been clear, that Christianity included success in battle.

|

|

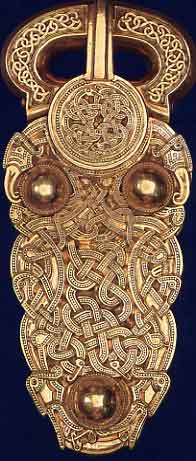

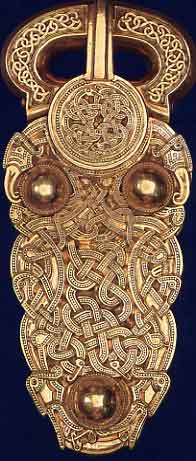

Sutton Hoo gold buckle |

|

625

|

Around 624 or 625, Raedwald, the High King of the East Angles, must have died, although we have no written evidence for this. After the battle on the River Idle, Bede gives Raedwald no further space. Raedwald was the greatest of the Wuffinga kings, and it is generally accepted that he was buried in a pagan ship burial at Sutton Hoo, in great splendour. The astonishing treasure of 'royal regalia', weaponry, and objects of everyday use gives an important insight into Anglo-Saxon aristocratic life at the beginning of the 7th Century. If it had not been for Sutton Hoo we would not be able to realise the incredible wealth, power, influence and connections of 7th Century kings in England. It was a far cry from the sometimes struggling rural villages of the East Anglian kingdom.

Although the Wuffings stronghold was in south-east Suffolk, they probably had royal outposts or vills at places like Coney Weston and Bedericsworth in West Suffolk. Raedwald had also presided over a great trading outpost arising at Ipswich. For two centuries London and York had been the only major east coast trading ports. The presence of the Wuffings on the River Deben caused Sutton to be a busy port, but the higher reaches of the Orwell at Gipeswic were to become far more important. Gipeswic is today known as Ipswich and was to remain a busy port until the 20th century.

From the humble villages like West Stow, to the great wealth of the rulers, it is clear that Anglo-Saxon society was highly stratified. In such a society there were obligations of protection, loyalty and service. The Wuffings drew their strength from the hundreds of little villages, like West Stow, which formed the backbone of their kingdom.

In turn, the people needed a strong king, for without the law and order that he could impose, they could not raise their crops and their families in safety.

|

|

627

|

Raedwald had apparently failed to make his own sons into Christians, so now it was King Edwin of Northumbria who was said to have persuaded the new King Earpwald of East Anglia to convert to Christianity.

However, it seems that there were still powerful adherents to the old ways who had mortal objections to a Christian rule in East Anglia.

Our main source for the period, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, tells us that the reign of Rædwald’s son Eorpwald ended in assassination and backsliding. He says in Book II, chapter 15:

"Not long after Eorpwald's acceptance of Christianity, he was killed by a pagan named Ricbert, and for three years the province relapsed into heathendom."

This little known pagan king called Ricbert may well have been another of Raedwald's sons,or one of the sons which his wife had produced from an earlier marriage. If so, he was brother or half brother to Sigeberht. It is considered that Ricbert ruled East Anglia from 627 to 629. As he took over by murdering Earpwald, and had rejected Christianity, this may have led Sigeberht, to consider claiming the throne himself and proclaiming Christian principles in the kingdom. Sigeberht seems to have been a stepson of Raedwald's, and son of Raedwald's queen, deriving his royal claim from this fact.

We can only wonder what effect this civil strife had on the inhabitants of the Lark valley, but no doubt sides were taken and blood was shed.

|

|

629

|

By 629 some unknown events transpired that allowed Sigeberht to take power, and he ruled East Anglia until about 636. According to Bede, Sigeberht had been in exile in Gaul, and there had been baptised into the Christian faith. Until this time the English kings do not seem to have accepted baptism until after they became kings. Sigeberht was the first man to already be a Christian before taking up power.

We do not know Ricbert's fate, as Bede merely says that Sigeberht succeeded to the kingship. However, it is implied in later events that Sigeberht had a military background, and so it is not unlikely that he gained power by force of arms.

Another man called Aethelric was also recorded as King at this time, and he may have shared the kingdom with Sigeberht by a division of territories. Bede appears to refer to Aethelric as Ecgric. He was the son of Eni, who was the brother of Raedwald, and so had some claim to the kingdom. If Sigeberht was only a stepson of Raedwald, and Aethelric his nephew, this might explain why a power sharing arrangement was agreed.

|

|

Walton castle below the waves |

|

631

|

Bede wrote that Sigeberht "laboured to bring about the conversion of his whole realm", and brought or encouraged Bishop Felix to provide a Christian education in East Anglia.

An infrastructure to support Christianity was thus introduced into the countryside of Saxon East Anglia when Bishop Felix established his see at a place called Dommoc, often claimed to be today's Dunwich. It now seems unlikely that Dunwich really existed as a centre at this time, and Dr Sam Newton argues that "Dommoc" was established at Walton Castle. Old Saxon shore forts like Walton, left behind by the Romans, seem to have been attractive to the first Christian foundations at this time.

Along with Christianity came literacy, a skill the pagan early Anglo-Saxons had not thought of value to them, and so had ignored. St Felix was from Burgundy and his Christianity was of the Roman tradition. He remained the first Bishop of the East Angles until his death in 647.

In 631, Anna, a brother of Aethelric, and son of Eni, must have been living in Exning. His father, Eni, was Raedwald's brother, so Anna was a nephew of Raedwald. This area, on the edge of the Fens, would have been rich in marshland products as well as located on the strategically vital Icknield Way. The Icknield Way was the only real land based route into East Anglia from Mercia. Anna was to become known as the Father of Saints, and in 631 his wife gave birth to Aethelthryth, who would grow up to became the founder of a Convent at Ely.

|

|

633

|

During Sigeberhts' reign a holy man came to his halls from Ireland called Fursa or Fursey. He brought with him his brothers Foillan and Ultan, as well as a number of other priests. It may be that Sigbert and Felix were looking for someone to run the school they had founded. The monastery and school was at Cnobheresburh, either at Burgh Castle near Yarmouth, or maybe at Caister on Sea.

|

|

635

|

Around 635, Sigeberht had founded a monastery at Bedericsworth, today called Bury St Edmunds. Bede states that he built the monastery for his own use. It was one of the earliest schools of English literacy, but it was not the type of structure whose ruins we see today, but was probably made of wood. The site may have been very close to the later abbey site at Bury. Bede recorded that Sigeberht now retired to live in his monastery

|

|

640

|

Penda of Mercia had a vision to establish Mercia as the most powerful state in the land. Mercia was landlocked, with no obvious physical boundaries. This meant that the kingdom was surrounded by potential hostile alliances. To counteract this threat, Penda had pursued a policy of establishing warlike supremacy over any other territory that he could. In 628 he had defeated the West Saxons. In 633 he had attacked and killed Edwin of Northumbria at Hatfield. The exact date when Penda attacked East Anglia is unknown to us, but D P Kirby has established that it must have been in about 640.

The location of Penda's attack upon East Anglia is also unknown, but it is likely that he attacked up the Icknield Way, exactly where the Fleam Dyke and Devil's Dyke were built for protection. King Aethelric was now in charge of all East Anglia and would have mustered an army in defence at the Dykes. His brother Anna, living at Exning, would be expected to play a major part in defending this area.

Thus, according to Bede, Sigeberht did not die peacefully in his monastery at Bury, but was killed in battle.

"The Mercians led by King Penda attacked the East Angles who, finding themselves less experienced in warfare than their enemies, asked Sigeberht to go into battle with them and foster the morale of the fighting men. When he refused, they dragged him out of the monastery regardless of his protests and took him into battle ... in the hope that their men would be less likely to panic ... under ... a gallant and distinguished commander. ... Mindful of his monastic vows, Sigeberht ... refused to carry anything more than a stick ... both he and King Egric were killed and the army scattered. These kings were succeeded by Anna, son of Eni."

Penda of Mercia was now overlord of East Anglia, and annual tributes had to be paid to him.

|

|

The Ixworth Cross |

|

645

|

Christianity now existed in many parts of East Anglia, even if it had not reached all of the common people. King Anna had been living at Exning for many years before he became King, and he and his family were Christians. So even the western parts of Suffolk were familiar with the Christian religion from its earliest introduction to the land of the Eastern Angles. This very high status garnet and gold cross pendant was found in a grave at Stanton, not far from Ixworth in Suffolk, in 1856. It indicates that the local nobility were possibly part of the royal family. They were well established as Christian, as well as extremely wealthy.

|

| c.650 AD |

It used to be thought that the period of occupation on the West Stow site lasted for about 200 years from 450 to 650. Around this time, over a period of perhaps 25 years, the village moved about a mile to the east perhaps around a new church. West Stow today is therefore centred on this new site. The original site was gradually deserted. There is evidence that other pagan Saxon settlements in Suffolk were abandoned at around this time, possibly to make a clean start on a new Christian site.

However, new research about a type of pottery called Ipswich ware, found at West Stow, now casts doubt on this dating. Please see the entry for 720 AD.

|

|

654

|

The Mercian king Penda had killed King Sigeberht of East Anglia in about 640, and continued to dominate Britain during the reigns of the next two kings of East Anglia. The first was King Anna, who had succeeded to the throne when both Sigeberht and Aethelric were killed.

Now, in 654, King Anna of East Anglia also met his death at the hands of the Mercians in the battle of Bulcamp, near Blyford in Suffolk. His son Jurmin was also killed along with many of their men. It was the last battle to be fought on East Anglian soil for many years. King Anna and his son were buried at Blythburgh according to the Liber Eliensis. According to Bede,

"Anna was killed by the same pagan King of the Mercians who had slain his predecessors", i.e., Penda. The Mercians are now thought to have continued to have dominated East Anglia, although the East Angles kept their own kings until around 865 when the Danes arrived.

Aethelhere now inherited the kingdom of East Anglia. He was the brother of the slain King Anna, and another son of Eni. He realised that he could not continue to hold out against Penda and his Mercian army, and decided to join him instead.

|

|

St Botolph's at Iken |

|

blank |

"654: Here King Anna was killed and Botwulf began to build a minster at Icanho". This reference in the Anglo Saxon Chronicles, versions A and E, is generally accepted to refer to Botolph building a religious site at Iken, located on the River Alde in East Suffolk. The site was probably on an island promontery, reached by a causeway which was cut off at high tide. Botolph was to become immensely influential in East Anglian Christianity, and his influence was seen in the later foundations at Wearmouth and Jarrow in Northumbria.

The site at Iken was only about an hour's walk from Rendlesham, where the Wuffings had their royal base. Botolph must have had close ties with the royal family to be allowed to do this, and its establishment may well have been as a memorial to Anna.

|

|

664

|

By 664 a plague was spreading across England, and was probably a major problem from 663 until 667. Archbishop Deusdedit died in Canterbury, as did King Erconberht of Kent. Cedd and most of his monks died at Lastingham, in Yorkshire. Plague may have played a part in the loss of old established pagan hamlets like West Stow.

In 664 King Aethelwald of East Anglia also died. He was the last of the four nephews of King Raedwald, who had ruled the kingdom for 35 years.

King Aethelwald of East Anglia was now succeeded by the obscure, but long - lived King Aeldwulf, who ruled until 713. Aeldwulf was the son of Aethelric, who had died in battle alongside Sighbert, fighting against Penda in 640. Aethelric was known to Bede as King Egric, and was Sighbert's brother. Little has been recorded of King Aeldwulf, but he ruled for 49 years, and succeeded in having a peaceful realm throughout that time. Christian institutions would become widely established throughout these years.

The first east anglian sceattas were probably minted in the reign of Aeldwulf.

|

|

St Etheldreda of Ely

|

|

673

|

Aethelthryth, the wife of King Ecgfrith of Northumbria, had determined to live a monastic life, and had been in a monastery near Berwick for about a year. In 673 she fled from Northumbria, pursued by soldiers, to return to her own estate at Ely.

She founded a double monastery at Ely, one part of which has been claimed to be the first nunnery in the country. Later she was to become known as one of the most famous saints of Anglo-Saxon England. Bede recorded that because of her life of purity and chastity, her body remained free of decay after death, which occurred in 679.

|

|

South Elmham minster

|

|

674

|

In about 673 or 674, during the reign of King Aeldwulf of East Anglia, a second Christian see was established in East Anglia at South Elmham to partner Dommoc.

|

|

680

|

By now there were two bishoprics or sees in East Anglia. One was well established, and was located at a place called Dommoc, and one was newly established at South Elmham, called Helmham in old English.

Monastic foundations were also believed to have been established at Clare and Sudbury in our area.

Most settlements built a church after this time, but were probably mainly of timber. Stone was not widely used until well into the 11th Century.

|

|

Timber Church at Brandon |

|

blank |

There is a middle Saxon site that has been excavated at Brandon, between the Little Ouse on one side and a marsh on the other, called Staunch Meadow. This seems to have become a literate and devout Christian settlement with a church. This was of timber and could have been a Monastery. Although its beginnings may have been around this time, it would develop over the next 200 years.

|

|

699

|

A prince of the Mercian royal blood called Guthlac decided to give up his career as a military man and become a monk. He built a hermitage dedicated to St Bartholomew in a desolate island in the Fens which became Crowland Abbey. A small community from Mercia established themselves here with Guthlac, and the Mercian Bishop Haedda, consecrated the site.

|

|

713

|

Following the death of King Ealdwulf, his son, King Aelfwald ruled East Anglia until 749 and was to be the last of the Wuffing dynasty. Aelfwald was a scholar, whcih in these times meant that he had learned to read and write and studied Christianity. He seems to have promoted Christianity and probably tried to emulate the developments in Northumbria. Certainly his kingdom had a tradition of literacy going back to Sigbert at Bedericsworth and Botolph at Iken. East Anglia seems to have had stronger Scandinavian affinities then any other early English kingdom, its most outstanding feature being the rite of royal ship funeral. In such a society the heroic epic poem Beowulf might have had its origins, perhaps to link the Wuffings with the Wulfings of Beowulf, an ancient and royal house back in the old country. Beowulf's action seems to take place in pagan Scandinavia from about 450-550, but its narrator is from a Christian society.

|

| c.720 |

During 2008 news of research by Paul Blinkhorn on the dating of Ipswich ware pottery would suddenly put a new complexion on the dating of the settlement at West Stow. Paul Blinkhorn’s study suggests that Ipswich Ware was not produced before the end of the 7th century with truly significant production and distribution not taking off until as late as the second quarter or middle of the 8th century. Until now it has been assumed

that production began in the second quarter or middle of the 7th century. ("Ipswich: Development and contexts of an urban precursor in the seventh century", by Christopher Scull of English Heritage.)

This gives a rather different view of when the village at West Stow was finally abandoned. The presence of Ipswich ware on the site now indicates that at least some inhabitants still lived at the site after say 720, and possibly up to 750. Hitherto it had been thought that the village was abandoned around 650 AD.

|

|

730

|

Excavation by Keith Wade for the Suffolk County Archaeology Service has revealed that the central part of the town of Ipswich was laid out during the reign of Ælfwald. As the trade capital of his kingdom this was presumably done with his support, or under his direction. A rectangular grid of streets linked the earlier quayside town northwards to an ancient trackway running east and west along the valley contour. This new grid of streets was divided into rectangular plots. The new town of the 8th century was built over the graveyards of the 7th century.

Pottery was becoming a large trade industry for Ipswich around Spring Road, and the making of combs from antlers was also important, judging from the finds of many archaeological digs.

|

|

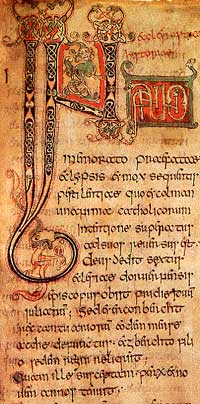

Bede's History

Bede's History |

|

731

|

By 731 when he was nearly 60, Bede had completed his Ecclesiastical History of the English People. It was in Latin, the language which could be read and understood throughout Europe, and was a church history of Anglo-Saxon England recording its saints and the miracles associated with their lives and, after death, their tombs.

|

Prepared for the St Edmundsbury History Project

by David Addy

Also "West Stow, Lackford Bridge Quarry

(WSW 030)" by Jess Tipper. Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service

March 2007

Report No. 2007/039

|