Pamphlet - Gangraena

Quick links on this page

Muggletonians etc 1652

Restoration Charles II 1660

Quakers in Bury 1682

Act of Toleration1689

Bottom of Page 1698

|

Alternative and Non-Conformist Religion

After the Civil War

|

1646

|

By this time there were a number of minority religions setting themselves up. Baptists, Ranters, Muggletonions, Quakers and Congregationalists all arose around this time. They were similar in many ways to Puritans so Oliver Cromwell mostly tolerated these religions as far as they did not interfere with public order.

Thomas Edwards (1593-1647) was the most outspoken and persistent Presbyterian opponent of these sects and of religious toleration. He wrote many pamphlets describing and attacking these "Errors, heresies, Blasphemies and pernicious practices", apparently with little regard for the truth of his allegations.

From February 1646 he published three parts of a work called "Gangraena" which included scandalous allegations and personal attacks on the senior figures of these new movements. One of those attacked was John Lanseter of Bury St Edmunds, a shopkeeper in Cook Row.

In Bury St Edmunds John Lanseter and seven others became founding members of a new movement who signed their Congregational Covenant on August 16th, 1646. Three of the signatories were women, a very unusual feature at the time. They were probably attracted by the teachings of Katherine Chidley. They were members of the puritan Presbyterian communion who currently controlled the two parish churches of St Edmundsbury. They were called Covenanters at first. Thus the New Independent Church was set up in Bury in 1646, later to be called the Congregational Church.

This church was set up with help from two London missionaries, Katherine Chidley and her son Samuel. They witnessed the Bury founding document or Covenant. They believed that the Church of England was evil and they intended to be fully separated from it.

After the Chidleys departed back to London, Lanseter remained the preacher of his new church.

|

|

Pamphlet - Lanseter's Lance

|

|

blank |

John Lanseter replied to "Gangraena" by publishing his own "Lanseter's Lance to Edwardes' Gangraena",

which described how he had travelled to London to confront Edwards, and to describe to him in detail where his allegations were incorrect and to ask for an apology in print. Edwards refused to accept Lanseter's account, and so Lanster felt obliged to reply in print. Unfortunately in this encounter he described his friendship with the Chidleys and the help they had given him, and this enraged Edwards further, who hated the idea of a woman preacher. He also hated her principles, calling her an old Brownist, and in a further pamphlet accused Katherine Chidley of being the real author of Lanseter's Lance. Samuel Chidley was also associated with the Levellers, another group accused of subversion.

The works of John Edwards had done much to divide Presbyterians from the Independents in a way which only benefitted the Royalists, who revelled in the dissension among their opponents.

By the end of 1646 the First Civil War had come to an end. The battle of Stow on the Wold was the last defeat of the last Royalist army.

Despite a largely puritan population, about 50 well to do Suffolk families remained pro-royalist, notably the Jermyn family at Rushbrooke. Sir William Hervey of Ickworth even raised a regiment for Charles I in the civil war.

In the years from 1643 to 1646 about 129 Anglican clergy from Suffolk's total of 517 were hauled up before Committees and accused of being scandalous or malignant. They were evicted from their livings and four fifths of their property was "sequestered" or confiscated. Virtually anybody who had accepted the directions of Bishop Wren in the late 1830's was put on trial. Even being an inadequate preacher brought penalties.

Lands confiscated from the Bishops was sold off to raise money to pay for off some of Parliament's debt mountain from the war.

|

|

1647

|

As hostilities seemed to be ending, Dr Stephens was reinstated as Headmaster of the Grammar School at Bury. He had shown that without him the school could not survive, despite his royalist views. Bury School had "become much decayed" in the two years since Stephens had been dismissed, and the school governors had to beg him to return, which he did, bringing his private pupils back with him.

Public disquiet about Matthew Hopkins and his witch hunts were to force Hopkins to abandon them by 1647. Although he is sometimes said to have been executed himself, he probably died of Tuberculosis.

George Fox, a Leicestershire puritan from a weaving family began to preach about his "great experience" of God and his speeches sometimes caused a shaking or quaking in his audience. Thus began the Quaker movement or Religious Society of Friends, who would soon become significant in local history.

At this time the Levellers were preaching religious freedom and condemning the Long Parliament for corruption and tyranny. The army tightened its grip. Parliament's presbyterian reforms seem to have failed by this time in Suffolk, as the system was not seen to be working.

|

|

Account of the riot

|

|

blank |

In 1644 Parliament had abolished Christmas, but in many places, this had been largely ignored. In June, 1647, a further Order in Parliament was passed as the Puritans tried to enforce this law. Christmas celebrations were banned and traders were ordered to open their shops as if it were a normal weekday. At Christmas this would result in a riot at Bury St Edmunds.

Some 150 Apprentices gathered on Christmas Day and were intent on enforcing shop closures and threatened to kill any traders that opened their doors.

They armed themselves with heavy clubs studded with nails. There was bloodshed reported in the Horse Market and at least two people were seriously injured. John Lansetter's shop in Cook Row was particularly targeted because of his well known position as an Independent and a pamphleteer.

Extreme Puritans viewed this riot as a "horrid plot and bloody conspiracy," as shown in the attached picture of a pamphlet issued at the time.

Perhaps the oddest thing about these riots is that the disputes were between what we would see as different degrees of Puritanism. The "established" version of Puritanism were the Presbyterians, while the rest were known as "Independents". One such Independent was John Lanseter or Lanceter of Cook Row in Bury St Edmunds. Lanseter was against Christmas as a pagan and Popish invention, and so he felt that he should continue to open his shop and trade as normal on Christmas Day. Royalist supporters, known as 'malignants' to the pamphlet author were happy to side with Prebyterians against Lanseter's stand and provoke a riot which threatened Lanseter's life and property.

Similar riots took place in Ipswich on Christmas Day as well. Both Bury and Ipswich were basically pro-parliament, and Ipswich had been a strong Puritan town for many years. Perhaps elsewhere this law was either accepted or quietly ignored.

|

|

1648

|

The years 1648 - 1649 are known as the Second Civil War. By the modern calender the uprisings were all in 1648, and Suffolk people participated in the troubles. This was a revolt of the provinces against centralisation and military rule. Although it is true to see it as another Royalist rising, it now included many moderate parliamentarians. It was fiercest in regions not paralysed by the effects of the first civil war, such as East Anglia, Kent, South Wales and Yorkshire. The revolts happened sporadically, one by one, and the army mostly was easily able to quell them.

At Stowmarket there was a "tumultuous assembly", and drums were beaten, but the authorities soon dispersed them.

At Bury St Edmunds a defiant crowd gathered on 12th May to protest about the Puritan restrictions on the old revels of May. Just as they were erecting a Maypole for the traditional , but long banned Maypole dancing, a troop of Lord Fairfax's cavalry rode into town. The rowdy crowd shouted out for "God and King Charles", and chased the no doubt bewildered cavalry out of town. Things escalated when the crowd decided to seize control of the powder magazine and put the town into a state of defence.

By now the crowd was said to number 600, with a further 100 mounted on horseback. Although this disturbance was called a Royalist rebellion, and indeed it was so, it was not a serious military threat. Parliament regained the town in two days on 15th May. The rioters are said to have "yielded to mercy". There does not seem to have been any organised leadership, and seems to have been a protest by working people.

Colchester was besieged by the Parliamentary army on 13th June, and finally surrendered after a two month siege. The parliament's New Model Army had Lord Thomas Fairfax as its Commander in Chief, and he led the siege. This was one of the bitterest engagements of the civil wars. In those two months until surrender on 28th August there was fierce fighting, heavy bombardments, and starvation of the town. Some 1500 people died, 186 houses were destroyed, and the garrison eat its 800 horses. The aftermath was a huge fine for the town, executions and exiles to the West Indies.

Sir Thomas Barnardiston of Kedington led one of the infantry regiments on Parliament's side in the siege.

By December 1648, John Lanseter's Independent Congregation in Bury seems to have dwindled and a new Covenant was signed with only Lanseter and two others remaining as signatories from the 1646 Covenant. This church flourished and survives to the present day as the Congregational Church in Whiting Street, Bury St Edmunds.

|

|

1649

|

By January 1649, by modern reckoning, the Rump of Parliament had already decided to put the King, Charles I, on trial for his so-called crimes. His worst offence to extreme Puritans, was to re-open the fighting after his defeats in the First Civil War. They believed it was the Will of God that they had prevailed in 1646. Thus when the king began the second war in 1648 he was going against God's will, as they saw it.

Much of England, including many Puritans, were appalled by the King's execution. They had only wanted to get him to govern with Parliament, not to remove him. Even senior activists like Nathaniel Bacon of Ipswich were in despair.

England now became a republic. In March the Monarchy and the House of Lords was officially abolished. The Anglican church was also abolished and people were no longer fined for not attending their local church. However, everyone was still expected to attend some form of religious worship on Sundays.

The Commonwealth was declared in June, and would last until 1660, an eleven year constitutional experiment.

In April 1649 the lands seized by Parliament from the Cathedrals was sold off. The Bishops' land had already been sold off in 1646. In July 1649 the Crown lands were sold to raise money. The post civil war period was the greatest transfer of land since the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Men like Ralph Margery of Walsham le Willows came out of the war on the victorious side, and was able to buy crown land in Bedfordshire and Lincolnshire. Another Roundhead soldier, John Moody of Bury St Edmunds, also bought crown lands.

Other Suffolk men got land in Ireland, having invested in its re-conquest in an arrangement in 1642. Sir Thomas Barnardiston of Kedington got 2,221 acres. Samuel Moody, a cloth merchant in Bury St Edmunds got 888 acres in Ireland, and lesser areas went to Philip Sparrow of Wickhambrooke, and John Fiske of Rattlesden.

Their most famous member of the sect known as the Ranters was Laurence Clarkson or Claxton, who joined the Ranters after encountering them in 1649. Under the influence of the Ranters, Claxton published his 1650 tract called "A Single Eye" in which he espoused the dissenting group's ideals. Clarkson opposed the idea of sin, considering it to be "invented by the ruling class to keep the poor in order." He felt that only the intention of an act, and nothing at all about its content, mattered to God. Ranters were regarded as heretical by the established Church and seem to have been regarded by the government as a threat to social order. They denied the authority of churches, of scripture, of the current ministry and of services, instead calling on men to listen to the divine within them.

|

|

1652

|

One of the strange Puritan sects that arose at this time were the Muggletonians. Lodowick Muggleton, (1609 - 1698), was a Puritan religious leader and anti-Trinitarian heretic whose followers, known as Muggletonians, believed he was a prophet.

After claiming to have had spiritual revelations, beginning in 1651, Muggleton and his cousin John Reeve announced themselves as the two prophetic witnesses referred to in Revelations 11:3. Their book, "A Transcendent Spiritual Treatise upon Several Heavenly Doctrines", was published in 1652. Muggleton was imprisoned for blasphemy in 1653, and his own followers temporarily repudiated him in 1660 and again in 1670. His attack on the Quakers led their leader, William Penn, to write "The New Witnesses Proved Old Hereticks" (1672).

Strangely, perhaps, the well known Ranter and pamphleteer, Laurence Clarkson, seems to have repudiated the Ranters by 1660 and become a Muggletonian.

|

|

1653

|

Oliver Cromwell, Commander of the Army since 1649, now led a call for a godly reformation of the country, as he was by now fed up with the Rump Parliament. The Rump were seen as too conservative for the army, so Cromwell dissolved them in April. He could not call free elections because he feared defeat of his ideas, so he called an 'assembly of saints'. In reality he hand-picked 140 men with his own ideological and religious leanings and they became known as the Nominated or Barebones Parliament, and ruled from July.

|

|

George Fox

|

|

1654

|

In 1652 George Fox (1624-1691) began his mission to bring his ideas about God to a wider audience. His followers were to become the Society of Friends, but were also to become referred to as Quakers, as a term of derision.

The Quakers had at first been a north of England movement, and in 1654 they sent a "mission to the south". Two quaker preachers duly arrived in Suffolk, and probably came to Haverhill. They were Richard Hubberthorne and George Whitehead, and although the east of England was "stony ground for Quakerism", they started a small group in Haverhill. Anthony Appleby was the most prominent of this small group.

On 6th July, 1654, John Lanseter, who had been a founding figure of the Independent movement in Bury St Edmunds and main signatory of the 1646 Covenant, was ejected from his own church for the sins of drunkenness and uncleanness. The record stated that "John Lanseter a member of this church, one of the foundation, for divers years an useful instrument for the good of the church, afterwards falling into the heinous and beastly sins of drunkenness and uncleanness was at length with great sorrow and lamentation when the whole church was met together, delivered over into the hands of Satan and cut off from the body about the 6th day of the fifth month commonly called July in the year of grace 1654."

|

|

1655

|

The Quakers had several practices which offended the Establishment of the day. They believed that there was no need for priests and referred to church buildings as steeple-houses, reserving the word church to refer to the congregation, not to a building. They refused to bow or doff their hats to the gentry and even refused to use the names of some weekdays and months where these derived from the names of pagan gods. They were often prosecuted for abusing ministers of the church. In 1655 however, George Fox the Quaker leader alienated his movement from the mainstream even further when he refused to pay church tithes and the Poor Law rates. Quakers were thus not tolerated by Cromwell in the way that the quieter splinter religions like congregationalists were.

The Quaker missionary Francis Howgill wrote in July 1655 that he held meetings in Norwich, Ipswich and Edmundsbury. One of the little rebellions of Quakers was to refuse to use the word saint, so St Edmundsbury would be called only Edmundsbury. Whatever the name, this is the the first evidence of quakerism in Bury St Edmunds. Unlike the reception in 1654, Howgill wrote that "Many large and great meetings we had....and we kindled a fire in that country."

Some other Quakers were arrested at Bures and two men, George Whitehead and John Harwood, were imprisoned in Bury gaol.

At this time the gaol in Bury was opposite the Corn Exchange, on the site of today's MVC Music and Video store. Today it would be described as being on the corner of Woolhall Street and Cornhill. They described it as "a low dungeon-like place, under a market house, our poor lodging being upon rye-straw on a damp earthen floor." For protesting against the conditions they were moved into a deeper dungeon, about four yards deep underground reached by a ladder. It had "but a little compass at the bottom and in the midst thereof an iron grate, with bars above a foot distant from each other and under the same a pit or hole, we knew not how deep". This gaol was eventually pulled down in 1770.

Catholics were also suffering. The estate of Euston Hall passed out of the hands of Edward Rookwood, a recusant, to Gorge Fielding, the Earl of Desmond. Rookwood had spent a fortune on the Hall before the war, but had suffered heavy fines for recusancy. In the end he had to sell up.

|

|

1656

|

Two Quaker preachers, George Harrison and Stephen Hubbersty had been "witnessing to the truth" in the streets of Bury St Edmunds in December 1656. The response was hostile and none of the inns or taverns would take them in, so they headed for the home of Anthony Appleby, a Quaker living in Haverhill, to pass the night. A mob soon assembled outside the house, shouting for the men to come out. Next day the mob reappeared, broke into Appleby's house and dragged out the two strangers, beating and kicking them to the end of the town.

The two men rode off to Kedington to lay complaints about their treatment to the local magistrate, Thomas Barnardiston. By now, Harrison was ill, partly from the beating no doubt, and partly from the winter weather and the long night ride to Haverhill. Barnardiston refused to hear their complaint because they would not pull off their hats to him and they departed for Coggeshall. Six weeks later George Harrison died and the record book of the Society of Friends recorded "whose blood will be charged upon thee, O Haverhill".

|

|

1657

|

In Haverhill the local puritans continued to harass the Quakers. John Sewell, a local Quaker was put in the stocks. His brother Ambrose and John Hall were seen speaking to him, and were sent to Bury goal as punishment. Anthony Appleby had goods distrained for refusing to pay his £20 tithe to repair the parish church.

In Bury similar persecution of Quakers had also continued.

Following an appeal to Cromwell himself, the Lord Protector made an order to release all 'Friends' in prison at Bury St Edmunds, Colchester and Ipswich. In all, thirty-three Quakers were set free in Bury. They included men like George Whitehead, who seemed to have been held since the arrests of 1655, and even one man, William Burroughs, of 80 years of age.

George Whitehead left Bury but was arrested again shortly after release, and flogged at Nayland.

|

|

1658

|

By 1658 Mary Beale was beginning her career in a small part time way, as a society portrait painter in London. Her father had been the Puritan Rector of Barrow, and her husband was also from a Puritan family. Their puritan circle seem to have supported her artistic endeavours.

|

|

Monarchy restored May, 1660

|

|

1660

|

General George Monck had been stationed in Scotland for five years. He had been suspected of Royalist involvement but he refused to clarify his position until he marched for London on 1 January 1660, arriving on 3 February. On the way Lord Fairfax seized York and handed it over to Monck.

Charles II was recalled unconditionally and he would rule until 1685. When Charles II was placed on the throne in May 1660 this event became known as The Restoration of the Monarchy. This came as a surprise in many parts of the country.

Along with rewards came some retribution. In Suffolk about 23 to 25 puritan clergy who had been intruded into their livings under the Parliamentary regime were evicted to reinstate the old incumbents. At Long Melford, the high churchman Robert Warren was reinstated to his living in May 1660, despite being 96. By November he voluntarily resigned his situation with a request that he be succeeded by Nathaniel Bisbie. Bisbie was probably also high church and thus immediately unpopular with a large section of his more "godly" congregation. He also attempted to reimpose all his tithes and dues of which the records had been destroyed by the mob in 1642. Bisbie was to leave behind him a considerable documentation of life and times for the parson at Long Melford in these years with the aim of protecting the rights of future holders of his office. Bisbie was himself to lose his living when he refused to swear allegiance to William of Orange in 1690.

|

|

1661

|

On 14 February 1661, the last of the New Model Army regiments paraded on Tower Hill where the soldiers symbolically laid down their weapons — and with them their association with the New Model Army and the "Good Old Cause". They were immediately ordered to take up arms again as troops of King Charles II's new standing army.

The so-called Cavalier Parliament was elected in April 1661. They passed a series of laws called the Clarendon Code, starting with the Corporation Act, 1661. They wanted to rid the boroughs of those Puritans who had elected the old Parliament.

At Bury as everywhere else, the corporation were now required to take the Oath of Supremacy, acknowledging the reinstatement of the crown's power in the land, and agreeing to take communion and renounce the covenant. More than half of Bury's corporation refused to swear the oath and in 1661-2 the Crown removed 19 members of the Bury St Edmunds corporation.

|

|

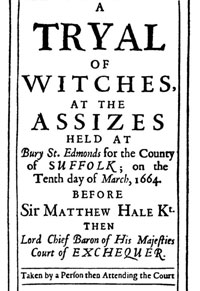

Account of witch trial

|

|

1662

|

Although the worst of the witch hunts ended in 1647, this superstition continued, and further executions resulted in 1662.

This event took place on 10 March 1662, when two elderly widows, Rose Cullender and Amy Denny (Deny / Duny), living in Lowestoft, were accused of witchcraft by their neighbours and faced 13 charges of the bewitching of several young children between the ages of a few months to 18 years old, resulting in one death.

After the reign of Charles II (1660 to 1685) witches were still brought to trial, but were no longer executed. The witchcraft laws were not finally abolished until 1736.

The year 1662 has become known as The Great Ejection followed the Act of Uniformity of 1662 in England. The Act of Uniformity prescribed that any minister who refused to conform to the Book of Common Prayer by St Bartholomew's Day (24 August) 1662 should be ejected from the Church of England.

Several thousand Puritan ministers were forced out of their positions in the Church of England, following The Restoration of Charles II. Although there had already been ministers outside the established church, the Great Ejection created an abiding concept of non-conformity.

Against the King's wishes, Parliament had passed the Act of Uniformity. This made the Church of England the official religion and all other denominations were forced underground. Puritans in the church were no longer tolerated.

The Church of England was restored along with its Bishops and Hierarchy. Having already evicted those clergy who had previously replaced evicted Anglican rectors, those puritan clergy who had always held their livings were now targetted. Some 56 ministers were evicted in Suffolk under this legislation, as well as the 23 or so, evicted in 1660.

The newly appointed Bishop of Norwich was Dr Edward Reynolds. He would be Bishop from 1661 until 1676, and had been a Presbyterian in the past. Although he followed the law in action against puritan ministers, he did not attempt to pursue them after eviction. Thus these dissenters were not persecuted as badly as they might have been.

As a result of the Uniformity Act, Stephen Scandarett, the fiery puritan preacher was ejected from his living at Haverhill. Scandarett was fervently anti-Quaker, even writing "An antidote against Quakerism". He had probably been behind incidents like the beating of the two Quaker preachers in 1656 in Haverhill. Scandarett may have continued to lead a clandestine congregation in the period from 1662 to 1672, when he would be licensed officially as a presbyterian preacher. This group represents the origins of the Old Independent Congregational Church, but the existing church of that name was not built until 1884. Following the same Act, old Samuel Fairclough, a Haverhill native, but now Vicar of Kedington, was also ejected from his living at the age of 68.

These evictions and the legislation behind them, is the reason for the division in the Protestant church in this country between Church and Chapel.

The Quakers refused to meet secretly and instead, met in public. They therefore took the brunt of official action against all non-conformists, and would suffer in this way for many years. However, by 1662, most Quakers had turned to pacifism, so avoiding the arrests for disorder that had characterised their early years.

|

|

1666

|

The non-conformist Quakers were still being arrested as they insisted upon meeting in public, but refused to attend Church of England services. For example, Edward Hall and his sister Ann were given 20 months imprisonment at Bury St Edmunds for not attending church. William Bennett had been released from Norwich Jail in 1665, but at Bury he was re-arrested and imprisoned for 8 years.

|

|

1668

|

Another Quaker rebellion against established religion was their refusal to pay tithes. In 1668, John and Ann Fryer were imprisoned at Bury for this offence, despite having seven dependent children.

|

|

1672

|

There was a brief period of toleration for non-conformists and Catholics when King Charles II issued a Declaration of Indulgence on 15th March, 1672. It became possible to apply for a license to worship in a private house. Thus quakers could avoid the obligation to attend public worship in the established church, and all the Quakers in prison were released.

Some 39 licences were issued to Presbyterian ministers in the South and West of Suffolk while the Congregationalists were more prevalent in the North-East around Lowestoft. At Bury a license was issued to Samuel Moody to hold meetings of a Presbyterian congregation at his house in Abbeygate Street. John Clarke's home at Bury was also licensed.

Stephen Scandarett, expelled from his Haverhill church living in 1662, was now allowed to get a license to become a presbyterian teacher. The house of Joseph Addy became the presbyterian meeting place in Haverhill. This congregation would become the Independent Congregational church in the next century.

Some time in the 1670s the Jesuits probably quietly moved into the Bishops Palace in the Abbey Grounds, and this became the base for their College of the Holy Apostles. Not all Catholics welcomed the presence of Jesuits. The Short family had always been Church Papists, willing to attend services of the established church while remaining Catholic. The Jesuits were the enemies of Church Papists, seeing this as an abandonment of their religion.

Parliament was aghast at the king's action on religious toleration, as was much of the population.

|

|

1673

|

Despite the licenses available in 1672, at least 7 Quakers were arrested at Bury for avoiding church attendance.

King Charles was forced to withdraw his Declaration of Indulgence because of the outcry in Parliament against him. His brother became Catholic in 1669, and Parliament feared that the Indulgence opened the door to a Catholic monarch again.

|

|

1674

|

In Haverhill Quaker Lane became so called when a Quaker burial ground and meeting house was established there. Quakers were fined and prosecuted throughout the 1660's and 1670's for their religious beliefs.

Thomas Milway became minister of the Bury Independent Church. He fostered Independent congregations in villages around Bury, particularly in Chevington, Rede and Hargrave.

|

|

1676

|

In 1676 a new register of recusants was drawn up. A register of Catholics who failed to attend a Protestant Church (ie recusants) was compiled in accordance with the 1606 'Act for the better discovering and repressing of popish recusants'. The churchwardens and constables of towns were required to bring to the Quarter Sessions all the recusants who had not attended a Church of England service for a month.

The Compton census of 1676 measured the sizes of the minority religious congregations. Wattisfield had 49 independents and Hepworth had 37. Bury had 167 dissenters and Clare had 300, Sudbury had 100, and Mildenhall had 66. The Bury non-conformists were divided across the existing parishes within the town. The parish of St James held 53 of the total number and St Mary's parish contained 114 of them.

As for Catholics, these tended to be clustered around local gentry families of that religion. There were 16 at Stanningfield, around the Rokewoods. There were 30 at Long Melford which had the Catholic gentry Martin, Harrison and Hinchlow families. Wetherden seems to have been the exception to this rule as this village had 18 Papists, with no local member of the gentry to protect them.

Bury had 40 Catholics, and despite being a Dissenters town, was the centre of Suffolk Catholicism. At some point over the next decade the East Anglian headquarters of the Jesuit College of the Holy Apostles was established in the Abbey Ruins in St Edmundsbury. The organisation had been set up in 1633 to provide for the needs of Roman Catholics in the eastern counties. It should be noted that both the catholic Rookwoods of Stanningfield and the Gages of Hengrave also had town houses in Bury, so their influence also reached well into the town.

|

|

1677

|

King Charles II was a well known womaniser who enjoyed the sporting life of Newmarket. But at night he worked on his dispatches in his bedroom, and he was well aware of the religious fervour around himself and the court. He was a practising Anglican, but was always suspected of harbouring Catholic sympathies. Charles knew that he had to support the protestant line if he was to retain his power. His brother James was much more open in his support for Catholicism, and had married the Catholic Mary of Modena, and himself converted to Catholicism, in 1673. Because the king had no legitimate heirs, his Catholic brother James thus became the heir apparent. James had a daughter called Mary, and to further establish his own Protestant credentials and those of the royal family, the King insisted upon a Protestant marriage for her. She was to marry the Protestant William of Orange. This marriage was arranged at the court in Newmarket, and without this arrangement the events which would follow in 1688 would never have happened.

|

|

1678

|

This was the year of a fictitious Popish plot, fabricated by Titus Oates to discredit Catholics. This led to the years 1679 to 1681 when Catholics were severely persecuted. In December William Gage, the Catholic owner of Hengrave Hall took a retinue abroad to avoid trouble. So did Catholics Sir Roger Martin of Long Melford, and Ambrose Rookwood of Coldham Hall. A number of other Catholics were imprisoned for a short time, including Henry Jermyn of Rushbrooke.

Some Catholics blamed the uncompromising attitude of the Jesuits for the persecution. At Bury, Richard Short junior was one of their most prominent critics, and subscribed to the idea that Catholics ought to swear an Oath of Allegiance to the monarch. Jesuits refused this idea because the monarch claimed to be Head of the Church in England, ahead of the Pope.

Meanwhile, the Quakers in Bury continued to be prosecuted for refusing to attend the Anglican church. In 1678 Robert Prick of Bury was imprisoned for refusing to pay towards repairs to the parish church, and for not paying "Easter offerings". He served 14 months.

|

|

Abbot's palace in 1680

|

|

1680

|

Following the dissolution of the Abbey of St Edmund in 1539, the monastery precincts were now in private hands. The Jesuit College of Holy Apostles was established within the old Abbot's Palace. This view shows the Abbot's palace, looking from the river to the east side of the ruins. It was drawn in 1727 by Edmund Prideaux, showing how it looked in about 1680.

|

|

1682

|

In 1682 the Society of Friends acquired a house for £50 in Long Brackland in Bury. It was probably not part of the site they still occupy today. Warren's map of 1748 shows the Quaker Meeting House in Long Brackland, but in the part still called Long Brackland today. In 1682 today's Long Brackland and today's St John's Street were one street called Long Brackland along its entire length. The modern street name of St John's Street did not arrive until the 19th century. Today's site in St Johns Street was acquired for the Quakers in 1752.

|

|

1683

|

In March, 1683, Newmarket suffered a great fire. This might have had the effect of saving the King, Charles II, from a plot to ambush and kill him. The King and the court were in Newmarket as usual at this time of year for the racing and other sporting activities. The royal party were expected to make their return journey to London on 1 April 1683, but as there was a major fire in Newmarket on 22 March, which destroyed half the town, the travel plans were changed. The races were cancelled, and the King and his brother, James, Duke of York, returned to London early. As a result, the planned attack at Rye House, near Hoddesdon, never took place.

The motive for the attack was the King's sympathy towards the Catholic religion, and his brother's known conversion to Catholicism in 1673.

The fire is said to have destroyed most of the north side of the High Street of Newmarket.

|

|

1684

|

Bury Quakers petitioned the King saying that 18 of their congregation had been held in Bury Gaol for 8 months, and that one, Joseph Chisnal, had died. We do not know the outcome of this petition.

|

|

1685

|

In 1685, King Charles II, also sometimes called the jockey king for his prowess on horseback, died suddenly on February 2nd, aged only 54. Although he had at least seven illegitimate children, his wife had suffered only miscarriages and stillbirths, and so he was succeeded by his brother James.

The Catholic James II came to the throne, and in his short three year reign he aimed to free Roman Catholics from the legal penalties imposed upon them by current laws. He had hoped that his presence on the throne would encourage the people to return to Catholicism of their own accord. But he had not understood how much the people were still suspicious of that religion and what it might mean for their future.

The anti-Catholic laws remained in place, but were unenforceable without incurring the new King's displeasure.

Emboldened by a Catholic sympathising king, the East Anglian headquarters of the Jesuit College of the Holy Apostles was more formally established in the Abbey Ruins in St Edmundsbury. The Abbot's Palace was probably purchased and new building work was carried out. These improvements were to be short lived, and destroyed by a mob in 1688. The College of Holy Apostles had been set up in 1633 to provide for the needs of Roman Catholics in the eastern counties. Sometimes clandestine, often peripatetic, it had very likely been in Bury St Edmunds since the 1870s.

For a brief period until 1688 the Town Corporation included Catholics, and Non Conformists as well as Anglicans. One such councillor was Dr Richard Short, who lived in Risbygate Street. The Shorts had always been "Church Papists", which meant that , although Catholic, they were prepared to attend the Church of England services, and thus avoid the penalties levied on recusants.

The Shorts came to Bury in the 1590s from Timworth, and there were several branches of the family. They were always Catholic, and usually followed the medical profession, having to qualify abroad because of their religion.

Because of their willingness to compromise over church attendance, the Shorts were opposed to the Jesuits presence in Bury St Edmunds. They opposed the new school and instead applied pressure on the Bury Grammar School to admit Catholics. Thomas and Richard Short served on the Bury Corporation, along with the new Catholic Mayor John Stafford, whose brother Nathaniel was a Jesuit.

Protestants were troubled by these changes, but were to become much more fearful after the news from France. In 1685 the Catholic king of France, Louis XIV, revoked the Edict of Nantes which had guaranteed the religious and civil rights of Huguenots. These were French subjects, mainly living in Normandy and Picardy, who followed the Protestant faith. All now had to convert to Catholicism or face persecution. Eventually this change would lead about half a million Huguenots to flee from France.

|

|

1687

|

King James issued Declarations of Indulgence which freed both Catholics and Dissenters from religious persecution, giving them civil rights and freedom to worship.

By 1687 King James II had found that the population had not spontaneously returned to Catholicism under his rule. Parliament would never repeal the Test Acts and the penal laws against Catholics of its own volition. So James II followed Charles II's lead and continued to insist upon nominating members of town corporations himself.

|

|

1688

|

In April 1688 the King ordered his Second Declaration of Indulgence, granting freedom of worship, to be read out in Church pulpits. Seven Bishops were arrested for denouncing the Declaration. One of these was William Sancroft from Suffolk, who was currently the Archbishop of Canterbury.

On 29th June the courts acquitted all the bishops to tumultuous public acclaim. Clearly the King was getting nowhere with his religious toleration policies using current tactics.

By now King James II was starting to enforce his will on local corporations to force them to adopt Catholic MP's, or at least, anti - Tory MP's. Lord Dover, the King's agent in this matter, sent the St Edmundsbury corporation a royal instrument ordering that 16 named members would be replaced by Crown appointees.

While this was happening, the King's second wife, Mary of Modena, had given birth to a son. The prospect of a Catholic dynasty spurred on Seven leading Whigs and Tories to issue an invitation to William of Orange on 30th June to defend English liberty and the Protestant religion.

By October, it was clear that the country would not put up with any more of this. William of Orange landed in the country at Torbay, on the 5th November supported by his 20,000 strong army and those Englishmen who wanted to ensure England remained protestant. James retreated back to London and then became unwell and lost his nerve and attempted to flee the country, trying as he goes to throw the great seal of England into the Thames. The Crown's nomination rights lapsed when James II finally fled the country on 23rd December, 1688.

Crowds took to the streets to celebrate. Unfortunately the king had advanced the Catholic cause too hard, and there was now a backlash against Catholics. Riots ensued in London and various other places, including Bury St Edmunds, with Catholic chapels being the first targets.

In early December, 1688, the rabble of Bury St Edmunds joined the Cambridge mob in a march on Cheveley in Cambridgeshire. Here, Henry Jermyn, the First Baron of Dover and a great supporter of James II, had a Catholic chapel at his magnificent home in Chevely. The Catholic chapel was pulled down and the house was wrecked. The Bury mob went home and was quiet for a few days.

The Catholic Mayor of Bury, John Stafford, was now accused of trying to blow up the Guildhall. Such rumours were inflamed when another rumour that Irish soldiers were marching on the town was spread.

On 20th December the Bury mob went on the rampage again. The recently built Jesuit college, known as the Mass House, in the old Abbot's Palace in the Abbey grounds was their main target. Both Jesuit school and chapel were pulled down, stone by stone. The remains were set on fire until it was destroyed down to ground level.

One Catholic had been killed trying to defend the chapel and the houses of two Catholics were torn down by the mob before the local gentry halted the violence. The Jesuits fled to the house of Thomas Burton at Beyton and made no attempt to return to Bury.

The mob, who were described as the Mobile, ie vagrants and paupers, now roamed the streets of Bury looking for more targets.

The homes of several Catholic members of the old corporation were ransacked, including John Stafford's. However, newspaper reports at the time said that they also rifled both Papists and Protestants, Test Men and Anti-Test Men, without distinction.

Test Men were those who supported the Anti-Catholic Test Acts, and thus should have been immune in these riots.

About 10 people were said to have died in these riots in Bury before the Magistrates restored order, imprisoning those they could catch.

Roman Catholic worship did not come out in the open in Bury again until the Westgate Street chapel was built in 1760 - 1762.

|

|

1689

|

Roman Catholics were now to be excluded from ever succeeding to the throne.

With the new royal family come permanent toleration for nonconformist Protestant religions, by way of the Toleration Act of 1689. Suffolk was a stronghold of nonconformity and its practitioners now became established and respectable. However, some clergy refused to swear allegiance to King William. They were called the non-jurors and about 23 Suffolk clergy were evicted for this offence. Three were in Long Melford, the rest spread across the county. The Melford evictions included Nathaniel Bisbie, who is known to us for his extensive documentation of the transactions of his living, and of local conditions. He died in 1695.

Nationally the Non-Jurors were Archbishop Sancroft and his six Bishops, and 400 lesser clergy, including the 23 in Suffolk.

William Sancroft was born in Fressingfield in Suffolk in 1617, but was educated at Bury St Edmunds Grammar School and at Cambridge university. He was a Royalist, and was Dean of St Pauls when it burnt down in 1666. He became Archbishop of Canterbury in 1678 and had resisted King James' Declaration of Indulgence in 1688, being imprisoned for it. But he felt it was wrong to de-throne a King in principle. He was suspended from office and evicted from Lambeth Palace. He returned to Fressingfield and lived like a hermit in a poor cottage until he died in 1693.

Other supporters of King James in exile were called Jacobites, and Norwich was a centre of East Anglian Jacobitism. Suffolk had few Jacobites apart from the religious Non-Jurors.

Most of the old Presbyterians had gone back to the official church after the Restoration, but a few had quietly kept to Presbyterian ideals. After the Toleration Act they started to build a Meeting House at the top of Churchgate Street. However, this is not the building which we see today, which came in 1711. They could do this provided they got a license from a JP.

The Toleration Act did not allow freedom of worship to Catholics, Jews or Unitarians. Neither did it allow Dissenters to hold public office or become MP's. They were still second class citizens. However, this amount of toleration was ahead of the continent, and was acceptable to the bulk of the population.

|

|

1691

|

Dr Francis Young has studied the Catholic congregation of Bury St Edmunds, and following the demise of the Jesuits in Bury, states that:- "the Shorts took advantage of the vacuum, and in 1691 they established a town mission led by a secular priest (meaning he belonged to no religious order) called Hugh Owen. Owen, who was born in the Isle of Man, remained in Bury until his death in 1741. In the early days, he may have ministered from the Short family home in Risbygate Street, but by the 1730s he was based at the Greyhound Inn on Cornhill, which later became the Suffolk Hotel and is now divided between Waterstone’s and Edinburgh Woollen Mill.

The Greyhound was owned by a Catholic landlord, William Adams. Owen sometimes also ministered at the Angel and at a coffeehouse called Hannibals."

Catholic worship thus continued in the town, but without a formal church or chapel.

|

|

1694

|

The last witch trial in Bury St Edmunds was in 1694 when Lord Chief Justice Sir John Holt, "who did more than any other man in English history to end the prosecution of witches", forced the acquittal of Mother Munnings' of Hartis (Hartest) on charges of prognostications causing death. The main charge was of Maleficia: casting a spell on her landlord causing his death. The second charge was of having a familiar imp in form of a polecat, and having two black and white imps. The chief charge was 17-years-old, the second brought by a man on his way home from an alehouse. The black and white imps were believed to have been two balls of wool. Sir John "so well directed the jury that she was acquitted". Sir John Holt bought Redgrave Hall in 1702, and he died in 1710, and was buried in Redgrave church.

|

|

1696

|

A plot was discovered to overthrow the new King and restore a catholic supremacy. One of the men involved was the Catholic Ambrose Rookwood of Stanningfield, who had, for a short time in 1688, been an Alderman on Bury Corporation. He had been one of James II's replacement corporation members. Along with some others he was executed at Tyburn for Treason.

|

|

1697

|

The religious group now referred to as Congregationalists was founded in Bury St Edmunds in 1646.

The church met in a variety of places until, in 1697, land was set aside in Whiting Street. Building work began immediately and although not completed until 1708, it was the first non-conformist building in Bury St Edmunds.

|

|

Celia Fiennes 1698 journey

|

|

1698

|

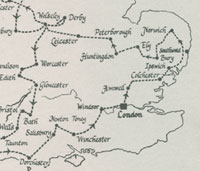

Celia Fiennes visited Bury St Edmunds in 1698, as part of a great circular tour of England from London up to Newcastle and Carlisle, and down to Cornwall, thence returning to London. She travelled the country between 1685 and 1710 and always recorded the trips in her journal.

Her mother was strongly non conformist and Celia inherited the family outlook on religion and whiggish politics.

Her stop at Bury was thus just one more small town on her grand tour. She thought 'the prospect was wonderful pleasant,' and 'there are a great deal of Gentry which lives in the town.' She also noted that there were many dissenters in the town, with 4 meeting places including those for the Quakers and Anabaptists.

|

|

|

Quick links on this page

Top of Page 1646

Muggletonians etc 1652

Restoration Charles II 1660

Quakers in Bury 1682

Act of Toleration1689

|

|

Next section

|

After the end of the Civil War and the transition into the 18th century the alternative religions begin to settle down and acquire premises.

|

Prepared for the St Edmundsbury Local History Project

by David Addy, July 17th, 2020

|